The Biopolitics of Population Control

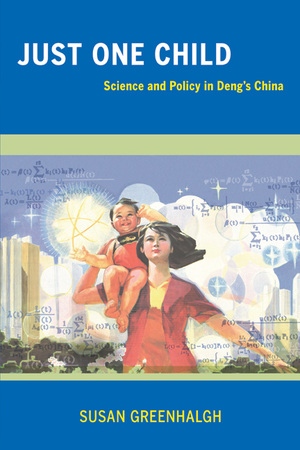

Just One Child

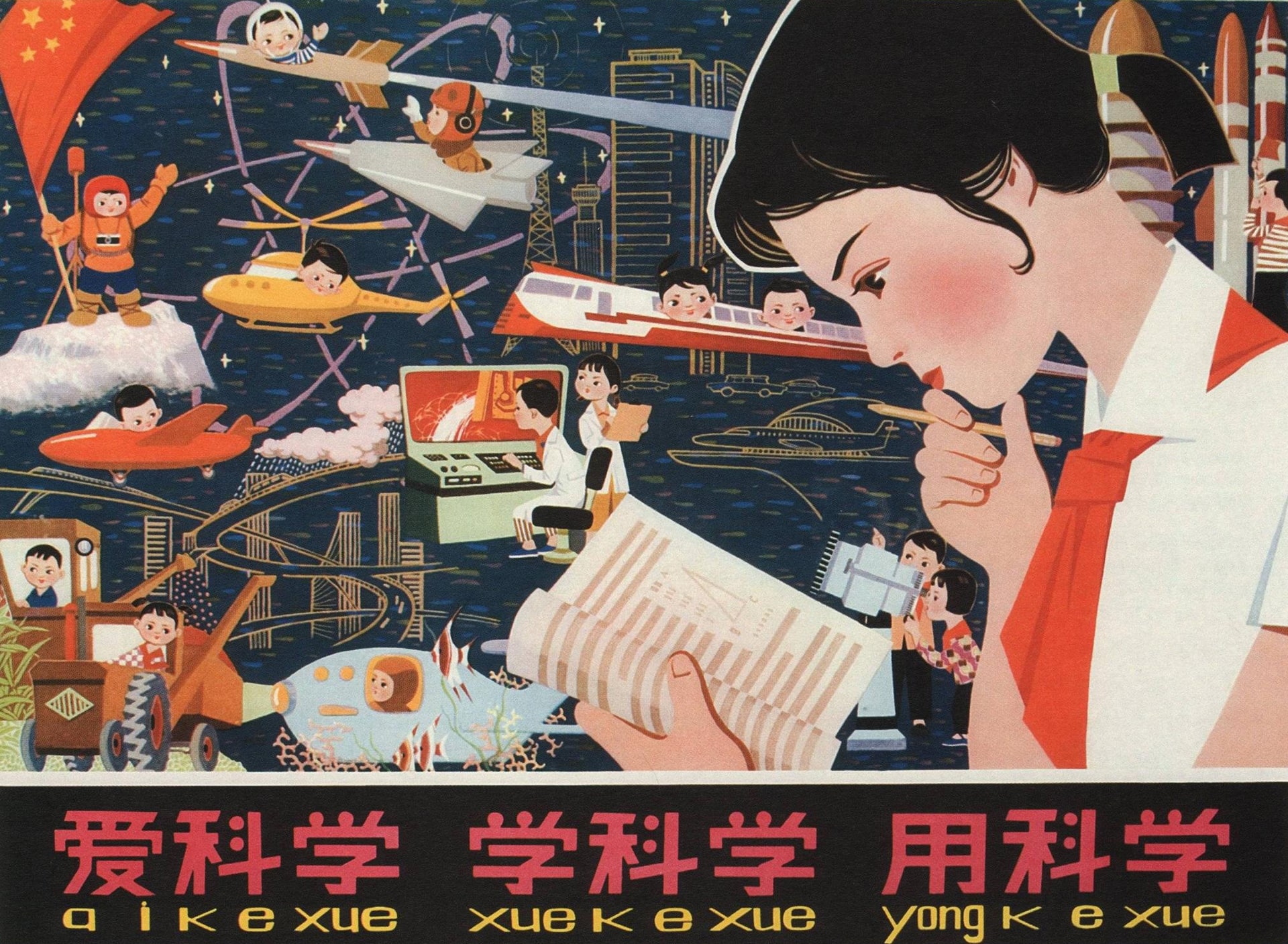

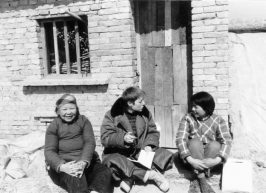

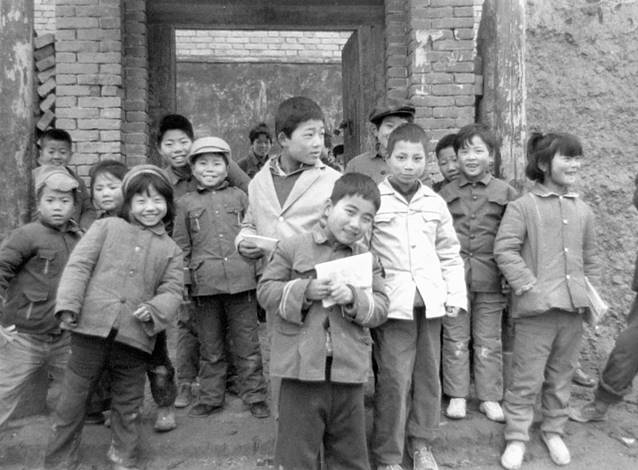

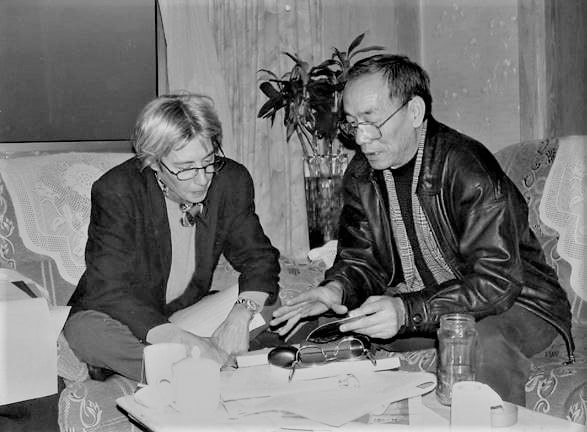

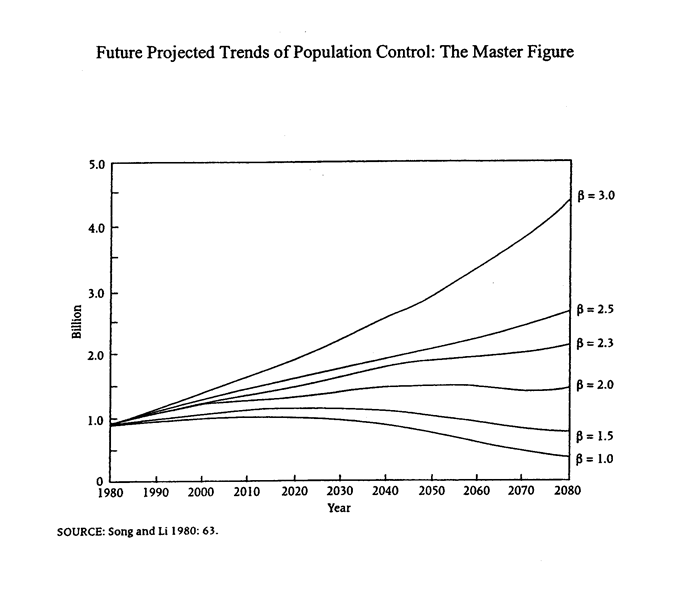

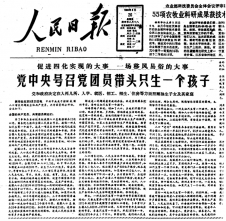

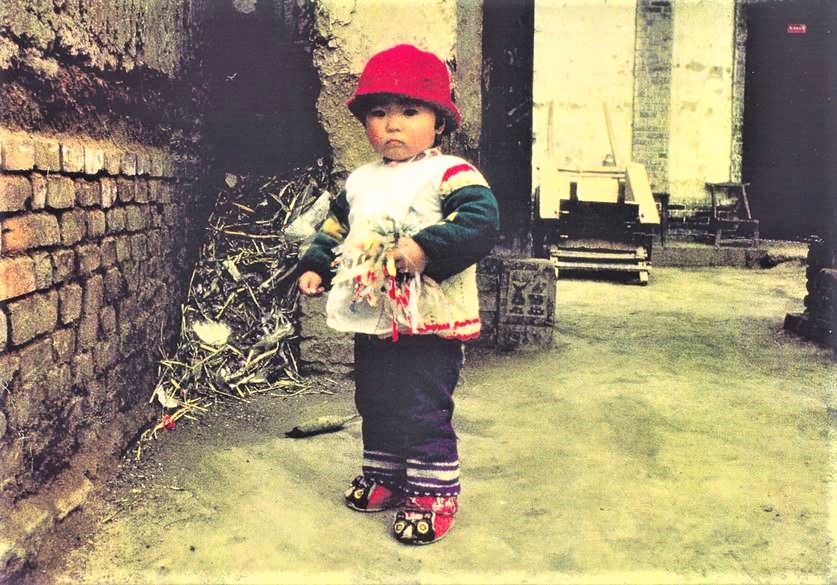

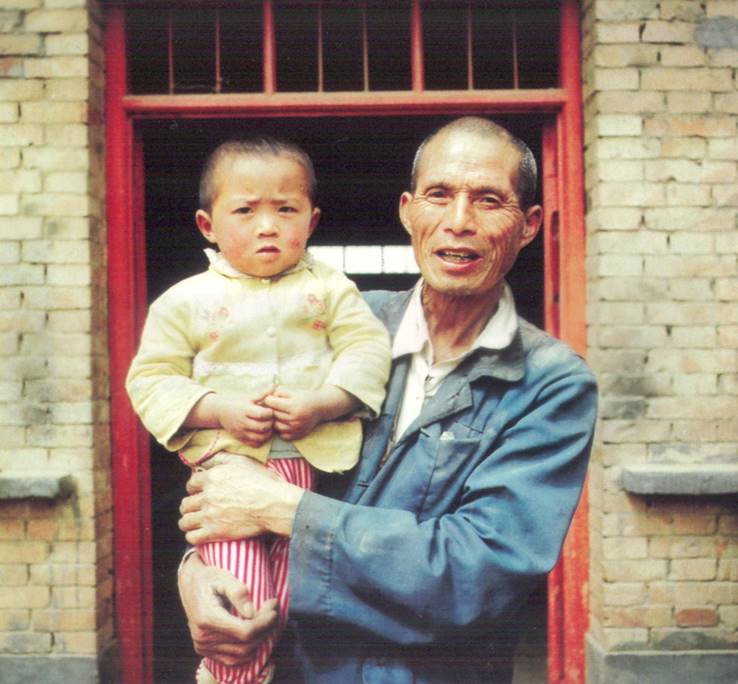

For many years, Greenhalgh’s core project was to understand the Chinese state’s efforts to transform China’s “backward masses” into the modern workers and citizens needed to make China a prosperous, globally prominent nation, as well as their effects on China’s society, culture, and politics. Her focus was the notorious one-child policy, which urged all couples, with some exceptions, to produce but one, well-bred child. Her ethnographic fieldwork of 20-plus years took her all over the country, from the villages of Shaanxi, where she spent seven months talking to farm families, to family planning model sites in Anhui, to the offices of top scientific advisors to the regime in Beijing. The story of the one-child policy turned out to be a story of the making of post-Mao China.

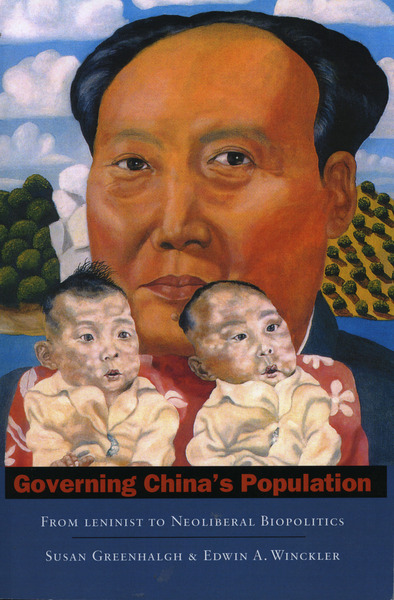

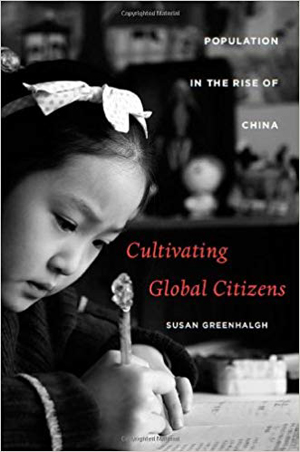

Three books published between 2000 and 2010 ask different questions about the policy and its role in governing and cultivating China’s society.

In 2015, with fertility falling to historic lows, China’s leaders finally abandoned the one-child rule, replacing it with a two-child (2016) and then three-child (2021) policy. Will the new policies persuade educated, ambitious young women and men to have more kids? It seems doubtful, but the government’s promotion of Confucian familism, and its expectation that women will (once again) save the nation by putting their own ambitions behind those of their country, will have deep social and cultural effects. Greenhalgh’s analysis suggests that the politics the new policies are now unleashing could remake China in ways we can scarcely imagine today.